The federal government’s plan to continue to regulate major resource projects despite a Supreme Court of Canada ruling that says those powers are largely unconstitutional is creating confusion and uncertainty in Ontario’s Ring of Fire.

A significant Indigenous stakeholder is making a plea for regulatory certainty, while a major mining company is warning that Canada’s weak standing on the global critical-minerals stage will only get worse.

The Supreme Court said earlier this month that the federal government’s broad-based environmental reviews around large mines and major infrastructure associated with those mines are unconstitutional. Ottawa must limit its oversight to certain defined areas clearly defined in the Constitution, the court said, such as fisheries, the bird population, species at risk and certain Indigenous rights.

The decision means that the provinces and territories have primary jurisdiction over regulating mining projects.

Since the ruling from the Supreme Court was in a reference case, one in which a province asked for an opinion, it is non-binding, but governments historically take such rulings seriously.

This week the federal government reiterated that because of the ruling, it intends to introduce legislation to change the 2019 Impact Assessment Act that will limit its oversight over resource projects. But Ottawa has not provided details on when that will happen and what the new regime will look like.

Companies with projects that are already subject to federal impact assessments are now facing major unknowns. The federal government said Thursday it will look at each individual case and determine whether it has jurisdiction over it or not.

Situated in Ontario’s far north, the undeveloped Ring of Fire is one of Canada’s highest-profile critical minerals projects and one of the projects most affected by the uncertainty. Three Ring of Fire road proposals are going through federal impact assessment studies.

Marten Falls, a remote First Nations community located 430 kilometres northeast of Thunder Bay, is involved in two proposals – leading one of the studies on a road project in the Ring of Fire corridor and co-leading another with Webequie First Nation.

The division of regulatory powers between the federal and provincial governments over the Ring of Fire “has to be clarified,” Marten Falls Chief Bruce Achneepineskum said in an interview.

His community has been working on one of the federal impact assessments for four years, and has been toiling for almost as long on an additional federally mandated regional assessment study on the Ring of Fire.

The regional assessment has been “daunting,” he said, given the huge demands on the community to provide large amounts of data and respond to countless requests around environmental impacts.

Amid confusion over whether some of the bureaucracy was even needed in the first place, Mr. Achneepineskum stressed the importance of timeliness around a massive resource project that could bring significant economic benefits to the community.

But rather than both levels of government working together to clarify the regulatory system in the wake of the Supreme Court decision, they appear instead to be on a “collision course,” he said.

Earlier this week, Ontario applied for judicial review around two large resource projects that are going through the Federal Impact Assessment system. The legal move is an attempt to prevent the federal government from making any further decisions in the areas the Supreme Court has deemed unconstitutional.

The federal government, however, is not backing down. Steven Guilbeault, the federal Environment Minister, said in a news conference on Thursday that the Ring of Fire is “clearly a federal area of jurisdiction,” as he vowed to assert Ottawa’s powers, particularly when it comes toIndigenous land.

Ontario’s legal moves, he said, are a “waste of time,” and something that “will only delay the approval of these projects.”

Both the Supreme Court ruling and the subsequent dispute between Ottawa and Ontario over resource jurisdiction is creating consternation at Ring of Fire Metals, the Australian-owned company hoping to build a nickel mine that could one day feed Canadian battery metals plants.

“It just brings more uncertainty,” said Kristan Straub, chief executive of Ring of Fire Metals. “Specifically at a time when Canada is trying to position itself, and we’re failing to position ourselves, as a safe, reliable supplier of critical minerals.”

Mr. Straub is particularly concerned about the federal government, indicating it may still exert discretionary powers over “designated projects” – large-scale resource projects – even though Supreme Court Chief Justice Richard Wagner expressly said Ottawa doesn’t have any constitutional powers in that area.

Earlier this week, Ottawa said it was pausing the environment minister’s power on new designated projects, but stopped short of saying it would do so permanently. Instead, the government said that consideration of new designated-project requests could potentially resume once amended legislation is in place.

“I don’t even think that there’s an ability to understand where the government is positioning themselves,” Mr. Straub said.

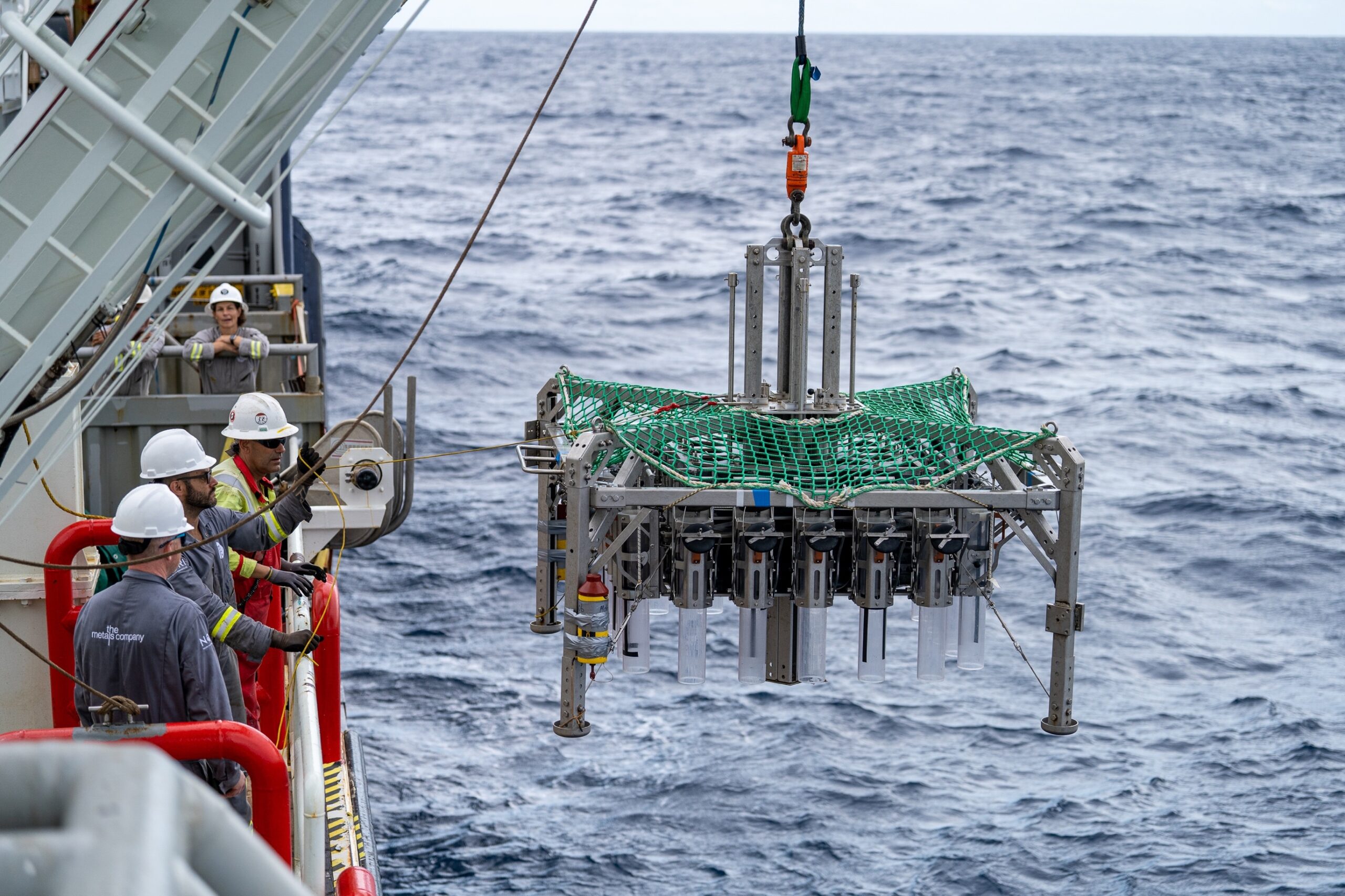

Last year, Australian resources giant Wyloo Metals Pty Ltd., which is controlled by billionaire Andrew Forrest, bought Canada’s Noront Resources Ltd. (now Ring of Fire Metals). The company’s Eagle’s Nest project was discovered in 2006 and has been held out repeatedly as Exhibit A for the languid pace of mining development and red tape in Canada.

Robin Junger, who is a partner of Indigenous law and environment with McMillan LLP, said the federal government’s primary focus should be moving forward with new legislation to rewrite fundamentally the Impact Assessment Act, rather than limping along with “unconstitutional legislation,” which opens it up to more legal challenges by the provinces.

“The Supreme Court’s decision is a more profound denunciation of the federal scheme than the government seems to be accepting,” he said.