Norway’s parliament approved on Tuesday commercial plans to open the Arctic Ocean to seabed mineral exploration, despite environmental groups and the fishing industry’s warnings that the move would risk the biodiversity of vulnerable ecosystems.

The bill, voted in by 80-20 by lawmakers, allows the exploration of around 280,000 sq km (108,000 sq m) of Arctic seabed, an area bigger than the size of the United Kingdom, between Norway and Greenland.

It is anticipated that an agreement on deep-sea mining in international waters could follow later in the year.

The move by the European country, where vast oil and gas reserves have made it one of the world’s wealthiest nations, has as goal to diversify its economy away from fossil fuels.

But it puts the country at odds with the EU and the UK, which have called for a temporary ban on the practice because of concerns about environmental effects.

“We’ve mapped vast areas in the northern Norwegian Sea since 2017. We’ve taken samples and collected data about minerals and metals found on the seabed,” the government said in a statement. “We’ve done this by means of our own expeditions, and also in cooperation with expert communities from universities.”

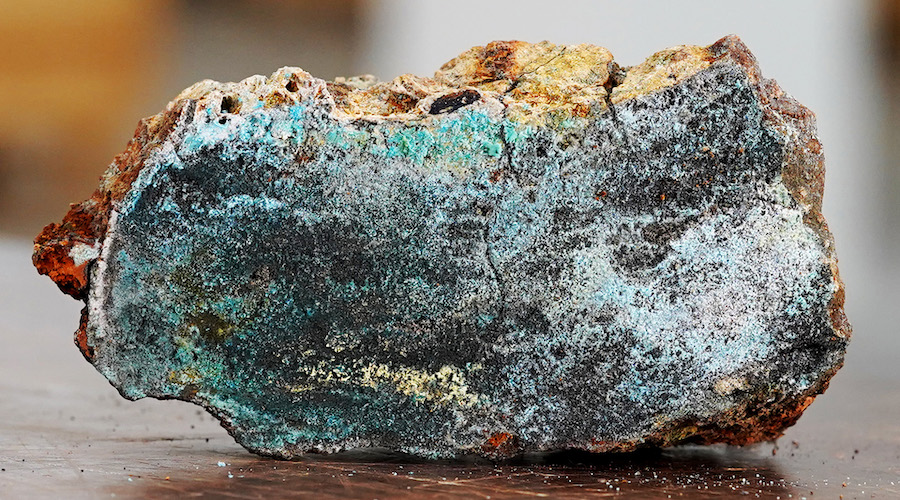

Norwegian continental shelf contains sulfide crusts, which may hold as much as 45 million tonnes of zinc. Manganese crusts, also present, may have around 3 million metric tonnes of cobalt, according to a white paper released by the government last June.

Critics were quick to react. Greenpeace called it was “a shameful day” for Norway. “It is embarrassing to watch Norway positioning itself as an ocean leader while giving the green light to ocean destruction in Arctic waters,” said Frode Pleym, head of Greenpeace Norway. “But this doesn’t end here. The wave of protests against deep sea mining has only begun.”

“Black mark” on Norway’s reputation

Kaja Lønne Fjærtoft, global policy lead for WWF’s No Deep Seabed Mining Initiative, said the organization was drawing a “small glimmer of hope” from the fact that extraction licences would still need parliamentary approval, an amendment added after strong international pushback.

The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) said the decision, would act as “an irrevocable black mark on Norway’s reputation as a responsible ocean state”.

Analysts highlight the risk of geopolitical tension in Europe’s northern and baltic region. The area Norway has opened up to exploration, in the Barents Sea and Greenland Sea, is near its Arctic islands of Svalbard. Oslo claims it has the sole right to mine in this area, but Russia, and the European Union dispute this claim.

According to the nation’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, the 280,000km2 (108,000 sq miles) along the mid-Atlantic Ridge, contains volcanic springs that surge from the Earth’s crust. They are believed to host an estimated 38 million tonnes of copper—more than the world’s approximate annual copper production.

A government-sponsored survey also found rare earth elements in polymetallic sulphides, or so-called “black smokers”, nearly 3,000 metres (9,842 feet) deep.

While international rules for seabed mineral extraction are yet to be set, Norway doesn’t need to wait, because it plans to search for minerals on its extended continental shelf.

A global agreement on deep-sea mining in international waters is expected to follow later in the year.

Proponents of deep sea mining argue that extracting raw materials from the seafloor will allow a faster transition to a low-carbon economy and could come at a lower environmentalcostthan terrestrial mining.

Scientists say very little is still known about the depths of the world’s oceans — only a small fraction of which humans have explored — and many are concerned about the impacts on these ecosystems already affected by pollution, trawling and the climate crisis.