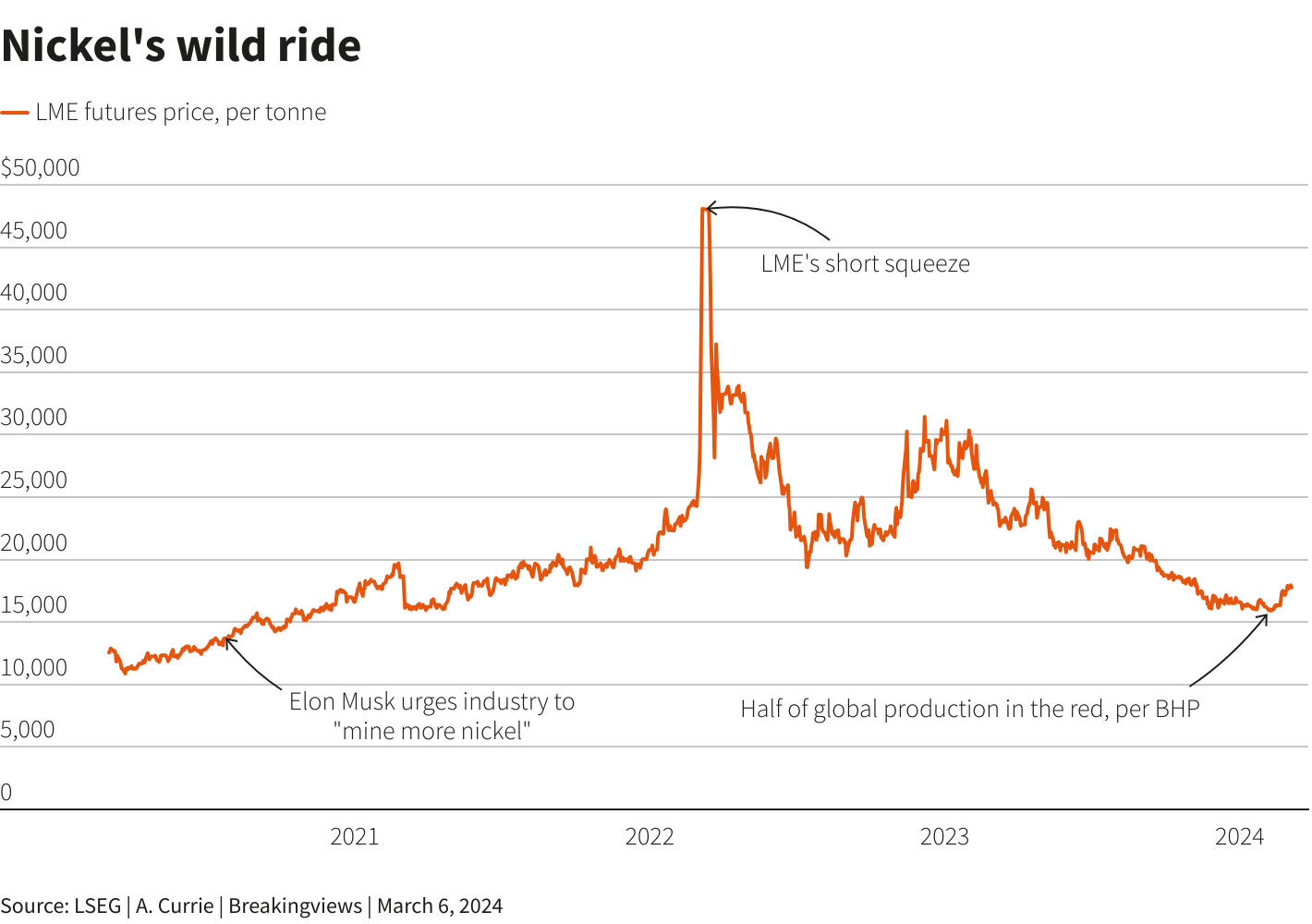

Please mine more nickel, okay?” Elon Musk urged, with a nervous chuckle, responding to a question about constraints to making electric batteries.

“Tesla will give you a giant contract for a long period of time,” the carmaker’s CEO said during a call with investors. That was July 2020.

Since then, use of the metal required to power electric vehicles has soared, rising 37% last year to 290,000 tonnes, according to research firm Adamas Intelligence.

Yet this year miners including BHP, Anglo American, Glencore, and Wyloo, owned by magnate Andrew Forrest, have been mothballing, writing down, or trying to sell their operations.

Blame the tumbling price of nickel, which by February had fallen below $16,000 a tonne on the London Metal Exchange, almost half its level a year earlier. That decline tipped half the world’s production of the commodity into the red, BHP calculates.

Despite a modest recovery to $17,700 a tonne in recent weeks, the ructions have lessons for the West’s energy-transition hopes.

Nickel increases the energy density of a battery, enabling it to store more power and add more range to electric vehicles than alternative chemistries like lithium iron phosphate. Up to 50 kilograms of the stuff goes into each power pack that uses it.

Supply has risen more than two-fifths over the past three years, almost entirely due to Indonesia. The archipelago increased its output of the metal tenfold over the past decade; most other countries flatlined or reduced production. Last year Indonesia accounted for 50% of the 3.6 million tonnes excavated globally.

Demand has proved less reliable. China last year appeared to use less nickel for steelmaking, which tends to account for around two-thirds of worldwide consumption. Production of electric-vehicle batteries, which scoop up a tenth of global output at best, is also hard to predict. Ford Motor, General Motors and other major carmakers have slowed their electric-vehicle plans.

Separately, power pack makers in the People’s Republic, like BYD and Contemporary Amperex Technology, met rising demand for their products in part by raiding their own stockpiled nickel, keeping the amount they bought to the same level as in 2022. Combined, that left global supply exceeding demand by as much as 10%, though new data suggests it may be nearer 4%, analysts at Macquarie argue.

The mismatch masks longer-term shifts.

Several years ago Indonesia’s government, eager to capture more value from the metal, ceased exporting the raw material and ramped up domestic processing. Incentives like 15-year tax holidays helped suck in investment from China, its main customer. Firms including Tsingshan and Lygend Resources & Technology built processing plants.

The two countries then developed and deployed a way to manufacture Class 1 nickel – defined as being at least 99.8% pure and the only type used in EV batteries – out of the lower-grade Class 2 supplies abundant in Indonesia.

That production came online around the time the LME experienced a spectacular squeeze in nickel in March 2022.

One of the problems worsening that crisis was a shortage of the metal in the bourse’s warehouses; the LME only trades and warehouses Class 1 nickel, which at the time did not include Indonesia’s innovation.

The LME last year started accepting some of it, which shifted pricing power to Indonesia, because the country can turn Class 2 into Class 1 nickel more cheaply than miners in developed countries can dig up the higher-quality metal.

All else being equal, these factors should have been manageable for miners from Australia to New Caledonia to Latin America.

Even at $16,000 a tonne the price was 20% higher than when Musk issued his 2020 plea. Inflation and other outlays, though, have pushed up expenses. The average cost of production Down Under is now $17,000 a tonne, 49% higher than in 2019 and 28% more than some Indonesian operations, calculates Mandala Partners in a report for The Chamber of Minerals and Energy of Western Australia.

Most solutions so far look piecemeal.

France this week agreed to swap into equity 320 million euros of loans to a New Caledonia operation held on French miner Eramet’s balance sheet. That, though, won’t do much to improve the profitability of the South Pacific territory’s nickel industry, which accounts for 6% of global supply. Glencore is mothballing its part-owned outfit there and wants to sell its stake.

Instead, governments and miners are coalescing around the idea of a green premium.

The concept is compelling. Turning lower-grade nickel into Class 1 material requires lots of energy, and Indonesian power relies heavily on burning coal. This means carbon emissions per tonne of Class 1 Indonesia nickel are up to six times higher than in Australia. Makers of electric cars – and their customers – might therefore pay more for batteries made with greener nickel.

Miners want the LME to take responsibility for the green premium by creating a separate contract for low-carbon nickel. Yet even if the exchange could define the parameters, the idea runs counter to a lesson of the 2022 squeeze: the nickel contract needed more liquidity.

Faced with sluggish EV sales and squeezed margins, carmakers want to minimize costs and secure supplies.

Indonesia is the only region that has markedly increased production in the past 10 years. That’s why Jakarta has successfully wooed auto and battery giants including Ford, LG Energy Solution, Volkswagen, Hyundai Motor Group and others to invest in the country’s nickel industry – often with Chinese partners.

On the one hand, that’s just business. But it’s also a consequence of leaving the supply of critical minerals at the mercy of the market.

Jakarta telegraphed its intention for years. Now the world’s car industry is dependent on a more carbon-intensive product with China’s fingerprints all over it – just as the US and Europe are trying to reduce their exposure to the People’s Republic.

Other materials used in EV batteries are also vulnerable. The price of lithium is down 80% in the past year, prompting some producers to slash output. Copper only declined around 15%, but Rio Tinto’s return on capital employed digging up the reddish-brown metal halved to just 3%, per LSEG data.

Meanwhile, more countries are following Indonesia’s lead: Ghana, Namibia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe are banning exports of raw lithium, while Chile, Bolivia and Mexico are at least partly nationalizing the industry.

Western governments could mimic Indonesia by granting tax holidays to critical minerals operations. Or perhaps overseas buyers will pressure Indonesia’s industry to be more environmentally conscious, pushing up costs. Musk may be the best hope for that: Tesla has unrivalled experience mapping its supply chain’s emissions.

Greening the archipelago’s operations is probably a years-long process, though. Even more reason for Australia, Canada, the Philippines and others to devise smart long-term strategies for critical minerals sooner rather than later.

(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist, Antony Currie. The opinions expressed are his own.)

(Editing by Peter Thal Larsen and Katrina Hamlin)