The mining world was pulled in all directions in 2023: the collapse of lithium prices, furious M&A activity, a bad year for cobalt and nickel, Chinese critical mineral moves, gold’s new record, and state intervention in mining on a scale not seen in decades. Here’s a roundup of some the biggest stories in mining in 2023.

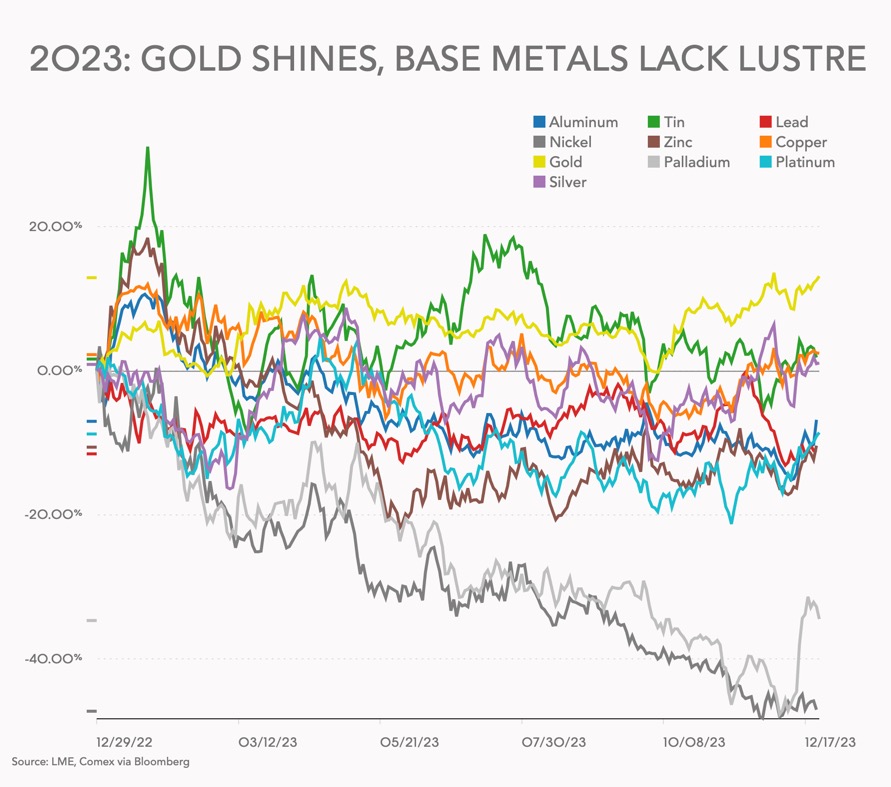

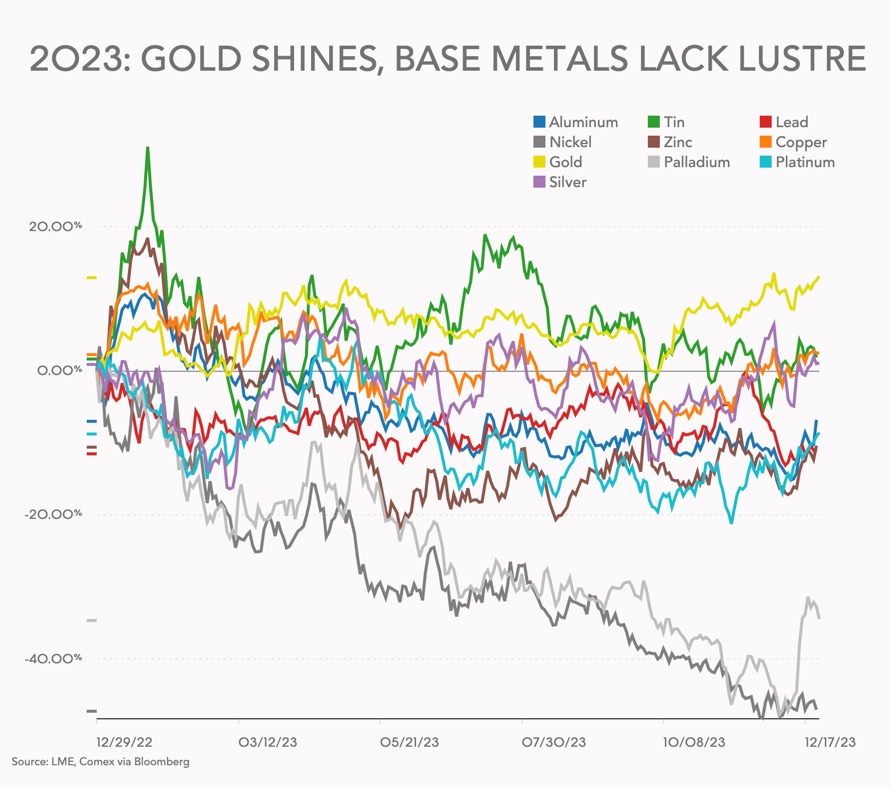

A year where the gold price sets an all-time record should be unalloyed good news for the mining and exploration industry, which despite all the buzz surrounding battery metals and the energy transition still represents the backbone of the junior market.

Metal and mineral markets are volatile at the best of times – the nickel, cobalt and lithium price collapse in 2023 was extreme but not entirely unprecedented. Rare earth producers, platinum group metal watchers, iron ore followers, and gold and silver bugs for that matter, have been through worse.

Mining companies have become better at navigating choppy waters, but the forced closure of one of the biggest copper mines to come into production in recent decades served as a stark reminder of the outsized risks miners face over and above market swings.

Panama shuts down giant copper mine

After months of protests and political pressure, at the end of November the Panama government ordered the closure of First Quantum Minerals’ Cobre Panama mine following a ruling by the Supreme Court that declared the mining contract for the operation unconstitutional.

Public figures including climate activist Greta Thunberg and Hollywood actor Leonardo Di Caprio backed the protests and shared a video calling for the “mega mine” to cease operations, which quickly went viral.

FQM’s latest statement on Friday said Panama’s government hasn’t provided a legal basis to the Vancouver-based company for pursuing the closure plan, a plan that the industries ministry of the central American nation said will only be presented in June next year.

FQM has filed two notices of arbitration over the closure of the mine, which has not been operating since protesters blocked access to its shipping port in October. However, arbitration would not be the company’s preferred outcome, said CEO Tristan Pascall.

In the aftermath of the unrest, FQM has said it should have better communicated the value of the $10 billion mine to the wider public, and will now spend more time engaging with Panamanians ahead of a national election next year. FQM shares have bounced in the past week, but is still trading more than 50% below the high hit during July this year.

Projected copper deficit evaporates

Cobre Panama’s shutdown and unexpected operational disruptions forcing copper mining companies to slash output has seen the sudden removal of around 600,000 tons of expected supply would, moving the market from a large expected surplus into balance, or even a deficit.

The next couple of years were supposed to be a time of plenty for copper, thanks to a series of big new projects starting up around the world.

The expectation across most of the industry was for a comfortable surplus before the market tightens again later this decade when surging demand for electric vehicles and renewable energy infrastructure is expected to collide with a lack of new mines.

Instead, the mining industry has highlighted how vulnerable supply can be — whether due to political and social opposition, the difficulty of developing new operations, or simply the day-to-day challenge of pulling rocks up from deep beneath the earth.

Lithium price routed on supply surge

The price of lithium was decimated in 2023, but predictions for next year are far from rosy. Lithium demand from electric vehicles is still growing rapidly, but the supply response has overwhelmed the market.

Global lithium supply, meanwhile, will jump by 40% in 2024, UBS said earlier this month, to more than 1.4 million tons of lithium carbonate equivalent.

Output in top producers Australia and Latin America will rise 22% and 29% respectively, while that in Africa is expected to double, driven by projects in Zimbabwe, the bank said.

Chinese production will also jump 40% in the next two years, said UBS, driven by a major CATL project in southern Jiangxi province.

The investment bank expects Chinese lithium carbonate prices could fall by more than 30% next year, dipping as low as 80,000 yuan ($14,800) per tonne in 2024, averaging at around 100,000 yuan, equivalent to production costs in Jiangxi, China’s biggest producing region of the chemical.

Lithium assets still in high demand

In October, Albemarle Corp. walked away from its $4.2 billion takeover of Liontown Resources Ltd., after Australia’s richest woman built up a blocking minority and effectively scuppered one of the largest battery-metals deals to date.

Eager to add new supply, Albemarle had pursued its Perth-based target for months, eying its Kathleen Valley project — one of Australia’s most promising deposits. Liontown agreed to the US company’s “best and final” offer of A$3 a share in September — a near 100% premium to the price before Albemarle’s takeover interest was made public in March.

Albemarle had to contend with the arrival of combative mining tycoon Gina Rinehart, as her Hancock Prospecting steadily built up a 19.9% stake in Liontown. Last week, she became the single largest investor, with enough clout to potentially block a shareholder vote on the deal.

In December, SQM teamed up with Hancock Prospecting to make a sweetened A$1.7 billion ($1.14 billion) bid for Australian lithium developer Azure Minerals, the three parties said on Tuesday.

The deal would give the world’s no.2 lithium producer SQM a foothold in Australia with a stake in Azure’s Andover project and a partnership with Hancock, which has rail infrastructure and local experience in developing mines.

Chile, Mexico take control of lithium

Chile’s President Gabriel Boric announced in April that his government would bring the country’s lithium industry under state control, applying a model in which the state will partner with companies to enable local development.

The long-awaited policy in the world’s second-largest producer of the battery metal includes the creation of a national lithium company, Boric said on national television.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in September said the country’s lithium concessions are being reviewed, after China’s Ganfeng last month indicated that its Mexican lithium concessions were being cancelled.

López Obrador formally nationalized Mexico’s lithium reserves earlier this year and in August, Ganfeng said Mexico’s mining authorities had issued a notice to its local subsidiaries indicating nine of its concessions had been terminated.

Gold to build on record-setting year

The New York futures price of gold set an all-time high at the beginning of December and looks set to surpass the peak going into the new year.

London’s gold price benchmark hit an all-time high of $2,069.40 per troy ounce at an afternoon auction on Wednesday, surpassing the previous record of $2,067.15 set in August 2020, the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) said.

“I can think of no clearer demonstration of gold’s role as a store of value than the enthusiasm with which investors across the world have turned to the metal during the recent economic and geopolitical turmoils,” said LMBA’s chief executive officer Ruth Crowell.

JPMorgan predicted a new record back in July but expected the new high to occur in the second quarter of 2024. The basis of JPMorgan’s optimism for 2024 – falling US interest rates – remains intact:

“The bank has an average price target of $2,175 an ounce for bullion in the final quarter of 2024, with risks skewed to the upside on a forecast for a mild US recession that’s likely to hit sometime before the Fed starts easing.”

Even as gold climbed new peaks, exploration spending on the precious metal dipped. A study published in November overall mining exploration budgets fell this year for the first time since 2020, dropping 3% to $12.8 billion at the 2,235 companies that allocated funds to find or expand deposits.

Despite the sparkling gold price, gold exploration budgets, which historically have been driven more by the junior mining sector than any other metal or mineral, dropped by 16% or $1.1 billion year-on-year to just under $6 billion, representing 46% of the global total.

That’s down from 54% in 2022 amid higher spending on lithium, nickel and other battery metals, a surge in spending on uranium and rare earths and an uptick for copper.

Mining’s year of M&A, spin-offs, IPOs, and SPAC deals

In December, speculation about Anglo American (LON: AAL) becoming the target of a takeover by a rival or a private equity firm mounted, as weakness in the shares of the diversified miner persisted.

If Anglo American doesn’t turn operations around and its share price continues to lag, Jefferies analysts say they can’t “rule out the possibility that Anglo is involved in the broader trend of industry consolidation,” according to their research note.

In October, Newcrest Mining shareholders voted strongly in favour of accepting the roughly $17 billion buyout bid from global gold mining giant Newmont Corporation.

Newmont (NYSE: NEM) plans to raise $2 billion in cash through mine sales and project divestments following the acquisition. The acquisition brings the company’s value to around $50 billion and adds five active mines and two advanced projects to Newmont’s portfolio.

Breakups and spin-offs were also a big part of 2023 corporate developments.

After being rebuffed several times in its bid to buy all of Teck Resources, Glencore and its Japanese partner are in a better position to bring the $9 billion bid for the diversified Canadian miner’s coal unit to a close. Glencore CEO Gary Nagle’s initial bid for the entire company faced stiff opposition from Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government and from the premier of British Columbia, where the company is based.

Vale (NYSE: VALE) is not seeking new partners for its base metals unit following a recent equity sale, but could consider an IPO for the unit within three or four years, CEO Eduardo Bartolomeo said in October.

Vale recruited former Anglo American Plc boss Mark Cutifani in April to lead an independent board to oversee the $26-billion copper and nickel unit created in July when the Brazilian parent company sold 10% to Saudi fund Manara Minerals.

Shares in Indonesian copper and gold miner, PT Amman Mineral Internasional, have surged more than fourfold since listing in July and are set to keep rising after its inclusion in major emerging market indexes in November.

Amman Mineral’s $715 million IPO was the largest in Southeast Asia’s biggest economy this year and counted on strong demand by global and domestic funds.

Not all dealmaking went smoothly this year.

Announced in June, a $1 billion metals deal by blank-cheque fund ACG Acquisition Co to acquire a Brazilian nickel and and a copper-gold mine from Appian Capital, was terminated in September.

The deal was backed by Glencore, Chrysler parent Stellantis and Volkswagen’s battery unit PowerCo through an equity investment, but as nickel prices slumped there was a lack of interest from minority investors at the stage of the $300 million equity offering which ACG planned as part of the deal.

Talks in 2022 to acquire the mines also fell through after bidder Sibanye-Stillwater pulled out. That transaction is now the subject of legal proceedings after Appian filed a $1.2 billion claim against the South African miner.

Nickel nosedive

In April, Indonesia’s PT Trimegah Bangun Persada, better known as Harita Nickel, raised 10 trillion rupiah ($672 million) in what was then Indonesia’s largest initial public offering of the year.

Harita Nickel’s IPO quickly turned sour for investors, however, as prices for the metal entered a steady and long decline. Nickel is the worst performer among the base metals, nearly halving in value after starting 2023 trading above $30,000 a tonne.

Next year is not looking great for the devil’s copper either with top producer Nornickel predicting a widening surplus due to lacklustre demand from electric vehicles and a ramp-up in supply from Indonesia, which also comes with a thick layer of cobalt:

“…due to the continuing destocking cycle in the EV supply chain, a greater share of non-nickel LFP batteries, and a partial shift from BEV to PHEV sales in China. Meanwhile, the launch of new Indonesian nickel capacities continued at a high pace.”

Palladium also had a rough year, down by more than a third in 2023 despite a late charge from multi-year lows hit at the start of December. Palladium was last trading at $1,150 an ounce.

China flexes its critical mineral muscle

In July China announced it will clamp down on exports of two obscure yet crucial metals in an escalation of the trade war on technology with the US and Europe.

Beijing said exporters will need to apply for licenses from the commerce ministry if they want to start or continue to ship gallium and germanium out of the country and will be required to report details of the overseas buyers and their applications.

China is overwhelmingly the top source of both metals — accounting for 94% of gallium supply and 83% of germanium, according to a European Union study on critical raw materials this year. The two metals have a vast array of specialist uses across chipmaking, communications equipment and defence.

In October, China said it would require export permits for some graphite products to protect national security. China is the world’s top graphite producer and exporter. It also refines more than 90% of the world’s graphite into the material that is used in virtually all EV battery anodes, which is the negatively charged portion of a battery.

US miners said China’s move underscores the need for Washington to ease its own permit review process. Nearly one-third of the graphite consumed in the United States comes from China, according to the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, which represents auto supply chain companies.

In December, Beijing banned the export of technology to make rare earth magnets on Thursday, adding it to a ban already in place on technology to extract and separate the critical materials.

Rare earths are a group of 17 metals used to make magnets that turn power into motion for use in electric vehicles, wind turbines and electronics.

While Western countries are trying to launch their own rare earth processing operations, the ban is expected to have the biggest impact on so-called “heavy rare earths,” used in electric vehicle motors, medical devices and weaponry, where China has a virtual monopoly on refining.