Chinese tycoons are turbocharging Indonesia’s aluminum industry with multi-billion dollar projects that rival the vast bets made on the country’s nickel riches roughly a decade ago, and threaten to shake up the global market for the metal.

Grappling with production curbs back home, companies like billionaire Xiang Guangda’s Tsingshan Holding Group Co., China Hongqiao Group Ltd. and Song Jianbo’s Shandong Nanshan Aluminum Co. are turning to Southeast Asia’s largest economy, ploughing cash into new smelters and refineries. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimates Indonesian aluminum production could rise five-fold by the end of the decade.

The question metals traders are now asking is whether Chinese capital can continue to pour investments into the country without ultimately tarnishing the outlook for the energy-intensive metal required for everything from soda cans to robotics and electric vehicles.

Nickel provides a cautionary tale. Indonesia accounted for roughly 7% global mine production a decade ago — it now accounts for closer to 60%, thanks to cheap coal power and Chinese smelters. Having underestimated that rapid rise, metals giants like BHP Group Ltd. have been forced to shutter operations in Australia and elsewhere. Even the Indonesian industry is now creaking under the weight of its own success.

“Over the next five years, Indonesia will become the focal point for the global aluminum industry” said Alan Clark, director of metals consultancy CM Group. “It’s really interesting to look at what’s happened in the global nickel sector and compare it.”

Granted, Indonesia’s reserves of bauxite — the raw material used to produce aluminum — are nowhere near as large as the low-grade nickel riches that took the industry by storm thanks to technological innovation. They are still enough to support a sizable smelting industry, backed by cheap labor and coal-fired power.

For Indonesia’s leaders, eager to develop a manufacturing sector that can provide employment and economic growth, the prospect of a repeat success is enticing, and motivated then-president Joko Widodo to ban the export of bauxite in 2023. His successor, Prabowo Subianto, has held firmly to a so-called “downstreaming” policy he hopes will help fund sweeping ambitions including universal free school meals and the establishment of a massive sovereign wealth fund.

A refinery typically costs around $1 billion to build — a hefty bet — but it’s a price worth paying for many Chinese companies eager to secure raw material.

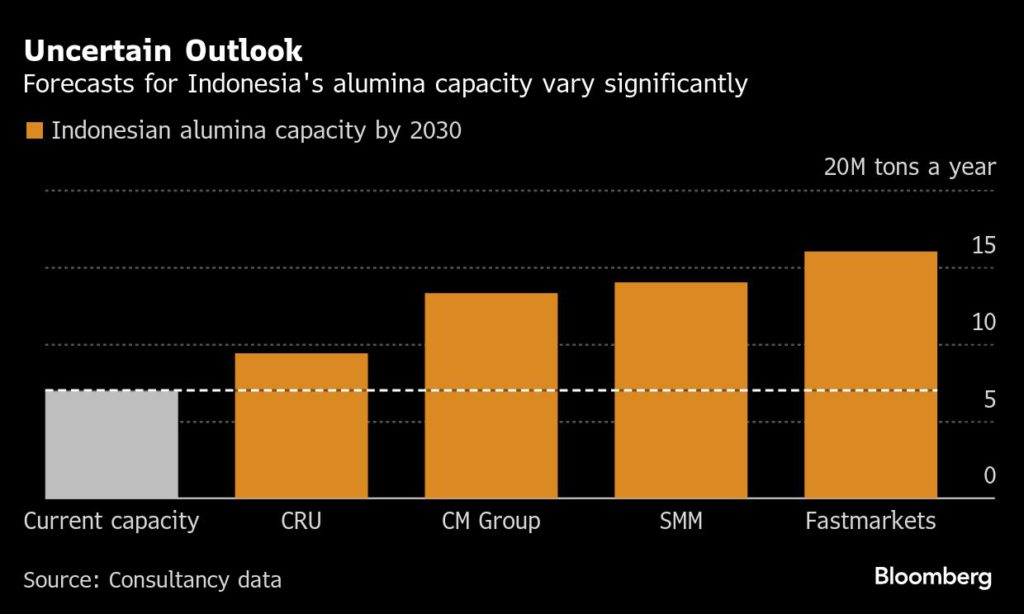

This year alone, three new alumina refineries, a key part of the aluminum production process, will begin working. At least another three are expected by the end of 2027, helping Indonesia’s capacity rise more than fivefold and catapulting the country into the top ranks of world producers, according to consultancy CRU Group.

And in smelting, Indonesia is also making great strides. Two plants are already operating in the country, and another four should be online by the end of the decade, according to Goldman Sachs.

Indonesia’s bauxite restrictions initially pushed China to buy from Guinea, the world’s largest producer. But the West African country is flexing its own supply dominance by canceling mining rights of firms that refuse to take the next step to construct refineries there, a move that only reinforced China’s desire to diversify.

Some Chinese metals tycoons are offering to bring their own plants piece by piece, or providing financial backing for local players unable to secure funding, according to Agustinus Tan, president director of bauxite producer PT Laman Mining.

“There are a few factories closing down, and they offered to acquire the machines,” said Tan, whose firm is looking to start building its own refinery next year. “It’s better to be far from the end product user than far from the raw material.”

Among the larger Chinese investors is Tsingshan, the stainless steel conglomerate that led the breakneck expansion of Indonesia’s nickel sector, thanks to dramatic scale and a ruthless focus on costs. Its first aluminum smelter was commissioned in 2023 and a significantly larger one is due to start production next year.

“When Tsingshan entered into aluminum, everyone was shocked,” said Andy Farida, an aluminum analyst at Fastmarkets Ltd. “They are diversifying.”

Much will depend on whether these firms will stick to their plans, even if economic headwinds continue to buffet the aluminum price in the near term. Citigroup Inc. analysts see minimal supply being added globally, including in Indonesia, if the metal stays close to its current levels around $2,500 a ton.

“Many in the market believe most of these plans will never materialize,” said Liu Defei, a veteran analyst formerly with miner Rio Tinto and Chinese researcher Antaike, pointing to questions around power supply. “If smelters can’t secure safe and affordable electricity — including cost-effective construction — they’re at a dead end.”

Coal — of which Indonesia has plenty — may again be called upon to power the industry, just as it did for nickel. But most critical of all will be Indonesia’s ability to mine enough bauxite to feed the ambitions of China’s metal men.

“I don’t think we should doubt what the Chinese are able to do,” said Farida. “If they are able to do what they did in nickel, it would not be surprising if the forecasts look far too low.”

(By Eddie Spence and Alfred Cang)